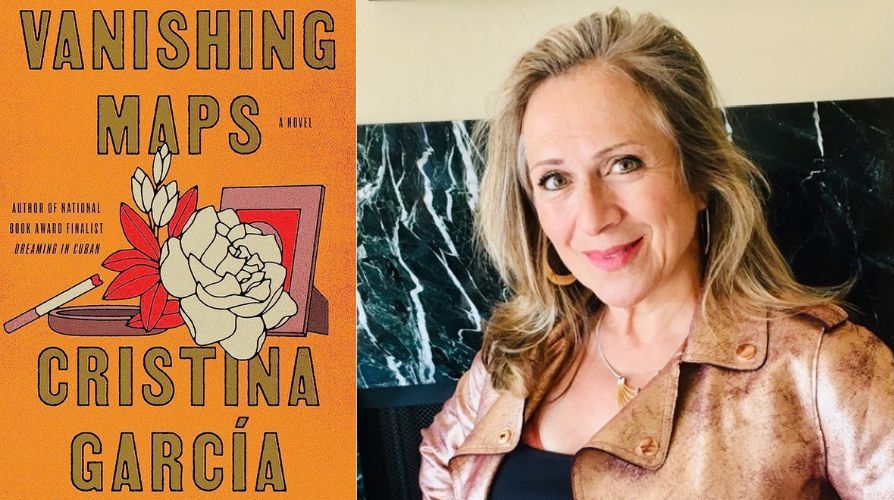

Cristina Garcia’s revelatory first novel, Dreaming in Cuban, a finalist for the 1992 National Book award, revolved around the del Pino family, its matriarch Celia, her children and grandchildren as they negotiate disagreements, dislocations, and reconnections in the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution.

With Vanishing Maps, her eighth novel, Garcia revisits the del Pino family twenty years later. Her scope has expanded to cover Miami, Los Angeles, Moscow, Prague, and Berlin, in addition to Cuba and New York, as family members reunite and reminisce. Time passing means shifts in perspective—regrets, painful memories, renewed love connections—all of which Garcia manages with great grace and wit.

What drew her back to this cast of characters? I asked the author/playwright. “My interest was ignited when I began adapting Dreaming in Cuban for the stage, at the behest of a young New York City director/producer named Adrian Alea,” she explains. “After a quarter-century, I reread the novel several times and, you might say, I got reacquainted with my own characters. Then I had the good fortune of having a talented group of actors literally bring these characters to life before my eyes. Their interpretations amplified my own understandings of the del Pino family. Central Works Theater Company in Berkeley did a lovely production of Dreaming in Cuban just last summer, directed by Gary Graves.”

I was enchanted by the transformation from novel to play when I attended a performance of Dreaming in Cuban one Sunday evening in July 2022 in a carefully distanced, masked small theater in Berkeley. Garcia distills the stories of three generations of women divided by La Revelución into a potent, at times poignant dreamscape.

Scenes with matriarch Celia del Pino, a stern and unflinching revolutionary, and her daughter Lourdes, an anti-communist exile who runs the “Yankee Doodle Bakery” in Brooklyn, are particularly powerful in delineating the conflict and heartbreak within this divided family. The ghost of Celia’s late husband Jorge appears from time to time, as if making amends. Celia teaches her eleven-year-old grandson Ivanito Russian and makes plans for his education in Moscow while his mother Felicia fades away in depression. Celia’s rebellious granddaughter Pilar, Lourdes’ daughter, maintains a spiritual connection with her abuela—and with her homeland—as she comes of age as an artist.

Vanishing Maps is a remarkable follow-up. It’s a haunting novel with freshly envisioned characters, including a fourth generation, whose lives, shaped by the past, offer resonant commentary on the present. Garcia tells me she wrote virtually all of Vanishing Maps under lockdown—“as the world as we knew it was morphing into a new, more frightening reality.”

Jane Ciabattari: In Dreaming in Cuban, you traced the reverberations of the 1959 revolution on each character, from Celia, the most ardent follower of El Líder to Celia’s daughter Lourdes, among the most anti-communist exiles. As the decades passed, and Castro died, new generations emerged. “Everyday Cuba fades a little more inside me and it’s only my imagination where our history should be,” you write. How did the revolution leave its mark on the twenty-first century?

Everything we’ve experienced and inherited continues to live inside us.

Cristina Garcia: I think the Cuban Revolution is one of those historical watersheds around which people continue to battle fiercely. On the one hand, millions of people were dispossessed and subjugated to a brutal dictatorship that continues to this day. Others would argue that Cuba has served as a beacon to small nations struggling against the political and economic dominance of larger, more exploitive countries. But no matter one’s perspective, Cuba’s interdependence with global events is undeniable (note the effects of the dissolution of the Soviet Union on the island). As a country always at the crossroads—and in the crosshairs—of history, Cuba continues to receive a disproportionate share of the world’s attention.

JC: Vanishing Maps is an intriguing title. How did it emerge? Was it your first choice?

CG: It seemed to me that the borders and alliances I knew as a child (I belonged to a geography club in fourth grade) and analyzed as an international relations graduate student, had irrevocably changed. When I came across these words—No border holds forever—in Günter Grass’s novel, Too Far Afield, I knew I was on the right track. The phrase also serves as my novel’s epigraph.

JC: I’m wondering how you settled on the characters whose stories unfold in Vanishing Maps. Celia del Pino in Havana and her five grandchildren are scattered around the globe—in Los Angeles, Miami, Moscow, and in Berlin (her one-time lover Gustavo, who is in touch after sixty-six years, is in Granada).

By juxtaposing these cities, you illuminate their histories—places with long-ago roots in Spain and the Soviet Union, and twentieth-century divisions between East (the USSR) and West (the U.S. and allies), followed by the fall of the Berlin Wall. the shifting allegiances among Havana and Miami Cubans. What was your process in drawing these global narrative lines?

CG: I was keenly interested in exploring the fallout from these myriad historical upheavals on the lives of the principal characters from Dreaming in Cuban. Not one of them is unaffected by the radically changing world around them. The maps they once relied upon—both internal and external—are indeed vanishing to unrecognizable degrees. And their divergent, diasporic journeys speak to the complexities of their Cuban and multiply hyphenated identities. How do they survive? Reinvent themselves? Find new moorings and allegiances? Vanishing Maps attempts to explore these issues through the struggles, mishaps, and comedies of four generations of the del Pino family.

JC: Ivanito Villaverde, in Berlin, works as a translator by day, and by night transforms into La Ivanita, a drag diva in the Berlin night club scene (he sometimes embodies the iconic La Lupe). From boyhood Ivanito has been an otherworldly creature. In Vanishing Maps we see him develop a halo that tightens at times; then he begins to see his late mother Felicia in increasingly disturbing visions. How do you think of this element of the novel, which in some ways echoes passages from Dreaming in Cuban?

CG: I’ve always invited the otherworldly into my works—elements we can only dimly perceive, or explain. There’s just too much that’s inexplicable, porous, and logic-defying for us to pretend otherwise. What I’m most interested in is trafficking in the borders between worlds, transgressing the purportedly fixed boundaries between life and death, between your history and mine, between competing ideas about time. Ultimately, I’m trying to acknowledge, often baroquely, that everything we’ve experienced and inherited continues to live inside us.

You can’t escape your history but there are certainly countless ways to deal with it.

JC: Ivanito’s artist cousin Pilar, and her son Azul, Celia’s great grandchild, come to visit him in Berlin. “It was as if his younger self were rising inside him like a watchful shadow, observing them both,” you write. “Ivanito sensed their histories converging, past and present melding into a dangerous, borderless whole.” Azul begins to see Ivanito’s ghostly mother, and Ivanito fears she has come to take him away. This element of the novel draws out Ivanito’s protective side, which, combined with his own fears and traumatic memories, brings a crisis. How did you set about ordering the scenes that draw upon family secrets, the layers of trauma evident within the generations, and tracing them back to Cuba?

CG: This is a variation of my response to your previous question. That the answers aren’t simple, and we may never know the full extent of their contours. But the (fictional) fact is that Ivanito, his dead mother, and his six-year-old nephew are inextricably linked. This tidal pull of family is inexorable whether people—or one’s characters—choose to ignore it. You can’t escape your history but there are certainly countless ways to deal with it. Those choices and negotiations and attempted escapes are, fundamentally, what my novels are about.

JC: Also visiting Berlin are Ivanito’s twin sisters Luz and Milagro, and two unexpected relatives, newly reunited twins Irina, who was raised in Moscow and Tereza, who grew up in East Berlin. The two had been separated at birth in Prague and reunited only months earlier at a lesbian tango party in Berlin. They’re still trying to unravel the mystery of their birth, which includes a Cuban father—Ivanito’s uncle. How unusual is it for such unexpected family connections to occur in communities of exiles and immigrants?

CG: There are so many fixed ideas about what Cubans are, and aren’t, on both sides of the Straits of Florida—and beyond—that are woefully out-of-date. Vanishing Maps tackles, in its own sinuous ways, the realities of a growing and far-flung Cuban diaspora—and the dislocations (and opportunities) that ensue when merged with other seismic historical events: the fall of the Berlin Wall; the dissolution of the Soviet Union; the persistence of the Cuban Revolution. These events continue to alter identity, belonging, and allegiances in profound ways. Under the circumstances, such an unexpected family connection might be unusual but it wouldn’t be unheard of. In my novels, Vanishing Maps included, the personal and the political are one.

JC: Seven photographs from Pilar’s past serve as interludes in the novel, offering glimpses of her at age two with her mother in 1961 (“It’s the moment we leave Cuba”), with Ivanito at CBGB’s in 1984, “stoned out of our minds,” and finally with the newborn Azul in 1993. How did you pick Pilar’s idiosyncratic “family album?”

CG: I wanted to have intermittent sections in Vanishing Maps that would be analogous to Celia’s letters in Dreaming in Cuban—providing context and family history in a distilled, poetic fashion. It seemed natural that Pilar Puente, who inherited her grandmother’s letters, would carry on this tradition in a visual format, as she’s an artist.

JC: What are you working on next? Another novel? Another play? Both?

CG: I’m working on a theater adaptation of Carolina De Robertis’s extraordinary novel, The President and the Frog, which I recommend to everyone. I also have another play, The Palacios Sisters, opening at the Gala Theater in Washington D.C. early next year. It’s an adaptation of Chekhov’s Three Sisters set in 1980s Miami. Very wild! As for another novel, I’m not quite sure. I’ve been working on one but also toying with the idea of not writing, of indulging my curiosity in new ways.

Vanishing Maps by Cristina Garcia is available from Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.